58 KiB

Git & GitHub Guide

Quick start: How Zulip uses Git and GitHub

This quick start provides a brief overview of how Zulip uses Git and GitHub.

Those who are familiar with Git and GitHub should be able to start contributing with these details in mind:

-

We use GitHub for source control and code review. To contribute, fork zulip/zulip (or the appropriate repository, if you are working on something else besides Zulip server) to your own account and then create feature/issue branches. When you're ready to get feedback, submit a work-in-progress (WIP) pull request. We encourage you to submit WIP pull requests early and often.

-

We use a rebase-oriented workflow. We do not use merge commits. This means you should use

git fetchfollowed bygit rebaserather thangit pull(or you can usegit pull --rebase). Also, to prevent pull requests from becoming out of date with the main line of development, you should rebase your feature branch prior to submitting a pull request, and as needed thereafter. If you're unfamiliar with how to rebase a pull request, read this excellent guide.We use this strategy in order to avoid the extra commits that appear when another branch is merged, that clutter the commit history (it's popular with other large projects such as Django). This makes Zulip's commit history more readable, but a side effect is that many pull requests we merge will be reported by GitHub's UI as closed instead of merged, since GitHub has poor support for rebase-oriented workflows.

-

We have a code style guide, a commit message guide, and strive for each commit to be a minimal coherent idea (see commit discipline for details).

-

We provide many tools to help you submit quality code. These include linters, tests, continuous integration with TravisCI, and mypy.

-

We use zulipbot to manage our issues and pull requests to create a better GitHub workflow for contributors.

Finally, take a quick look at Zulip-specific Git scripts, install the Zulip developer environment, and then configure your fork for use with TravisCI.

The following sections will help you be awesome with Zulip and Git/GitHub in a rebased-based workflow. Read through it if you're new to git, to a rebase-based git workflow, or if you'd like a git refresher.

Set up Git

If you're already using Git, have a client you like, and a GitHub account, you can skip this section. Otherwise, read on!

Install and configure Git, join GitHub

If you're not already using Git, you might need to install and configure it.

If you are using Windows 10, make sure you are running Git BASH as an administrator at all times.

You'll also need a GitHub account, which you can sign up for here.

We highly recommend you create an ssh key if you don't already have one and add it to your GitHub account. If you don't, you'll have to type your GitHub username and password every time you interact with GitHub, which is usually several times a day.

We also highly recommend the following:

- Configure Git with your name and email and aliases for commands you'll use often. We recommend using your full name (not just your first name), since that's what we'll use to give credit to your work in places like the Zulip release notes.

- Install the command auto-completion and/or git-prompt plugins available for Bash and Zsh.

Get a graphical client

Even if you're comfortable using git on the command line, having a graphic client can be useful for viewing your repository. This is especially when doing a complicated rebases and similar operations because you can check the state of your repository after each command to see what changed. If something goes wrong, this helps you figure out when and why.

If you don't already have one installed, here are some suggestions:

- macOS: GitX-dev

- Ubuntu/Linux: git-cola, gitg, gitk

- Windows: SourceTree

If you like working on the command line, but want better visualization and navigation of your git repo, try Tig, a cross-platform ncurses-based text-mode interface to Git.

And, if none of the above are to your liking, try one of these.

How Git is different

Whether you're new to Git or have experience with another version control system (VCS), it's a good idea to learn a bit about how Git works. We recommend this excellent presentation Understanding Git from Nelson Elhage and Anders Kaseorg and the Git Basics chapter from Pro Git by Scott Chacon and Ben Straub.

Here are the top things to know:

-

Git works on snapshots: Unlike other version control systems (e.g., Subversion, Perforce, Bazaar), which track files and changes to those files made over time, Git tracks snapshots of your project. Each time you commit or otherwise make a change to your repository, Git takes a snapshot of your project and stores a reference to that snapshot. If a file hasn't changed, Git creates a link to the identical file rather than storing it again.

-

Most Git operations are local: Git is a distributed version control system, so once you've cloned a repository, you have a complete copy of that repository's entire history. Staging, committing, branching, and browsing history are all things you can do locally without network access and without immediately affecting any remote repositories. To make or receive changes from remote repositories, you need to

git fetch,git pull, orgit push. -

Nearly all Git actions add information to the Git database, rather than removing it. As such, it's hard to make Git perform actions that you can't undo. However, Git can't undo what it doesn't know about, so it's a good practice to frequently commit your changes and frequently push your commits to your remote repository.

-

Git is designed for lightweight branching and merging. Branches are simply references to snapshots. It's okay and expected to make a lot of branches, even throwaway and experimental ones.

-

Git stores all data as objects, of which there are four types: blob (file), tree (directory), commit (revision), and tag. Each of these objects is named by a unique hash, the SHA-1 has of its contents. Most of the time you'll refer to objects by their truncated hash or more human-readable reference like

HEAD(the current branch). Blobs and trees represent files and directories. Tags are named references to other objects. A commit object includes: tree id, zero or more parents as commit ids, an author (name, email, date), a committer (name, email, date), and a log message. A Git repository is a collection of mutable pointers to these objects called refs. -

Cloning a repository creates a working copy. Every working copy has a

.gitsubdirectory, which contains its own Git repository. The.gitsubdirectory also tracks the index, a staging area for changes that will become part of the next commit. All files outside of.gitis the working tree. -

Files tracked with Git have possible three states: committed, modified, and staged. Committed files are those safely stored in your local

.gitrepository/database. Staged files have changes and have been marked for inclusion in the next commit; they are part of the index. Modified files have changes but have not yet been marked for inclusion in the next commit; they have not been added to the index. -

Git commit workflow is as follows: Edit files in your working tree. Add to the index (that is stage) with

git add. Commit to the HEAD of the current branch withgit commit.

Important Git terms

When you install Git, it adds a manual entry for gitglossary. You can view

this glossary by running man gitglossary. Below we've included the git terms

you'll encounter most often along with their definitions from gitglossary.

branch

A "branch" is an active line of development. The most recent commit on a branch is referred to as the tip of that branch. The tip of the branch is referenced by a branch head, which moves forward as additional development is done on the branch. A single Git repository can track an arbitrary number of branches, but your working tree is associated with just one of them (the "current" or "checked out" branch), and HEAD points to that branch.

cache

Obsolete for: index

checkout

The action of updating all or part of the working tree with a tree object or blob from the object database, and updating the index and HEAD if the whole working tree has been pointed at a new branch.

commit

As a noun: A single point in the Git history; the entire history of a project is represented as a set of interrelated commits. The word "commit" is often used by Git in the same places other revision control systems use the words "revision" or "version". Also used as a short hand for commit object.

As a verb: The action of storing a new snapshot of the project's state in the Git history, by creating a new commit representing the current state of the index and advancing HEAD to point at the new

fast-forward

A fast-forward is a special type of merge where you have a revision and you are "merging" another branch's changes that happen to be a descendant of what you have. In such these cases, you do not make a new mergecommit but instead just update to his revision. This will happen frequently on a remote-tracking branch of a remote repository.

fetch

Fetching a branch means to get the branch's head ref from a remote repository, to find out which objects are missing from the local object database, and to get them, too. See also git-fetch(1).

hash

In Git's context, synonym for object name.

head

A named reference to the commit at the tip of a branch. Heads are stored in a file in $GIT_DIR/refs/heads/ directory, except when using packed refs. (See git-pack-refs(1).)

HEAD

The current branch. In more detail: Your working tree is normally derived from the state of the tree referred to by HEAD. HEAD is a reference to one of the heads in your repository, except when using a detached HEAD, in which case it directly references an arbitrary commit.

index

A collection of files with stat information, whose contents are stored as objects. The index is a stored version of your working tree. Truth be told, it can also contain a second, and even a third version of a working tree, which are used when merging.

pull

Pulling a branch means to fetch it and merge it. See also git- pull(1).

push

Pushing a branch means to get the branch's head ref from a remote repository, find out if it is a direct ancestor to the branch's local head ref, and in that case, putting all objects, which are reachable from the local head ref, and which are missing from the remote repository, into the remote object database, and updating the remote head ref. If the remote head is not an ancestor to the local head, the push fails.

rebase

To reapply a series of changes from a branch to a different base, and reset the head of that branch to the result.

Get Zulip code

Zulip uses a forked-repo and rebase-oriented workflow.. This means that all contributors create a fork of the Zulip repository they want to contribute to and then submit pull requests to the upstream repository to have their contributions reviewed and accepted. We also recommend you work on feature branches.

Step 1a: Create your fork

The following steps you'll only need to do the first time you setup a machine for contributing to a given Zulip project. You'll need to repeat the steps for any additional Zulip projects (list) that you work on.

The first thing you'll want to do to contribute to Zulip is fork (see how) the appropriate Zulip repository. For the main server app, this is zulip/zulip.

Step 1b: Clone to your machine

Next, clone your fork to your local machine:

$ git clone git@github.com:christi3k/zulip.git

Cloning into 'zulip'

remote: Counting objects: 86768, done.

remote: Compressing objects: 100% (15/15), done.

remote: Total 86768 (delta 5), reused 1 (delta 1), pack-reused 86752

Receiving objects: 100% (86768/86768), 112.96 MiB | 523.00 KiB/s, done.

Resolving deltas: 100% (61106/61106), done.

Checking connectivity... done.

Note: If you receive an error while cloning, you may not have added your ssh key to GitHub.

Step 1c: Connect your fork to Zulip upstream

Next you'll want to configure an upstream remote repository for your fork of Zulip. This will allow you to sync changes from the main project back into your fork.

First, show the currently configured remote repository:

$ git remote -v

origin git@github.com:YOUR_USERNAME/zulip.git (fetch)

origin git@github.com:YOUR_USERNAME/zulip.git (push)

Note: If you've cloned the repository using a graphical client, you may already

have the upstream remote repository configured. For example, when you clone

zulip/zulip with the GitHub desktop client it configures

the remote repository zulip and you see the following output from git remote -v:

origin git@github.com:YOUR_USERNAME/zulip.git (fetch)

origin git@github.com:YOUR_USERNAME/zulip.git (push)

zulip https://github.com/zulip/zulip.git (fetch)

zulip https://github.com/zulip/zulip.git (push)

If your client hasn't automatically configured a remote for zulip/zulip, you'll need to with:

$ git remote add upstream https://github.com/zulip/zulip.git

Finally, confirm that the new remote repository, upstream, has been configured:

$ git remote -v

origin git@github.com:YOUR_USERNAME/zulip.git (fetch)

origin git@github.com:YOUR_USERNAME/zulip.git (push)

upstream https://github.com/zulip/zulip.git (fetch)

upstream https://github.com/zulip/zulip.git (push)

Step 2: Set up the Zulip development environment

If you haven't already, now is a good time to install the Zulip development environment (overview). If you're new to working on Zulip or open source projects in general, we recommend following our detailed guide for first-time contributors.

Step 3: Configure Travis CI (continuous integration)

This step is optional, but recommended.

Zulip Server is configured to use Travis CI to test and create builds upon each new commit and pull request. Travis CI is free for open source projects and it's easy to configure for your own fork of Zulip. After doing so, TravisCI will run tests for new refs you push to GitHub and email you the outcome (you can also view the results in the web interface).

First, sign in to Travis CI with your GitHub account and authorize Travis CI to access your GitHub account and repositories. Once you've done this, Travis CI will fetch your repository information and display it on your profile page. From there you can enable integration with Zulip. (See screen cast.)

Using Git as you work

Know what branch you're working on

When using Git, it's important to know which branch you currently have checked out because most git commands implicitly operate on the current branch. You can determine the currently checked out branch several ways.

One way is with git status:

$ git status

On branch issue-demo

nothing to commit, working directory clean

Another is with git branch which will display all local branches, with a star next to the current branch:

$ git branch

* issue-demo

master

To see even more information about your branches, including remote branches,

use git branch -vva:

$ git branch -vva

* issue-123 517468b troubleshooting tip about provisioning

master f0eaee6 [origin/master] bug: Fix traceback in get_missed_message_token_from_address().

remotes/origin/HEAD -> origin/master

remotes/origin/issue-1234 4aeccb7 Another test commit, with longer message.

remotes/origin/master f0eaee6 bug: Fix traceback in get_missed_message_token_from_address().

remotes/upstream/master dbeab6a Optimize checks of test database state by moving into Python.

You can also configure Bash and Zsh to display the current branch in your prompt.

Keep your fork up to date

You'll want to keep your fork up-to-date with changes from Zulip's main repositories.

Note about git pull: You might be used to using git pull on other

projects. With Zulip, because we don't use merge commits, you'll want to avoid

it. Rather that using git pull, which by default is a shortcut for git fetch && git merge FETCH_HEAD (docs), you should use git fetch

and then git rebase.

First, fetch changes from Zulip's upstream repository you configured in the step above:

$ git fetch upstream

Next, checkout your master branch and rebase it on top

of upstream/master:

$ git checkout master

Switched to branch 'master'

$ git rebase upstream/master

This will rollback any changes you've made to master, update it from

upstream/master, and then re-apply your changes. Rebasing keeps the commit

history clean and readable.

When you're ready, push your changes to your remote fork.

Make sure you're in branch master and the run git push:

$ git checkout master

$ git push origin master

You can keep any branch up to date using this method. If you're working on a

feature branch (see next section), which we recommend, you would change the

command slightly, using the name of your feature-branch rather than master:

$ git checkout feature-branch

Switched to branch 'feature-branch'

$ git rebase upstream/master

$ git push origin feature-branch

Work on a feature branch

One way to keep your work organized is to create a branch for each issue or feature. Recall from how Git is different that Git is designed for lightweight branching and merging. You can and should create as many branches as you'd like.

First, make sure your master branch is up-to-date with Zulip upstream (see how).

Next, from your master branch, create a new tracking branch, providing a descriptive name for your feature branch:

$ git checkout master

Switched to branch 'master'

$ git checkout -b issue-1755-fail2ban

Switched to a new branch 'issue-1755-fail2ban'

Alternatively, you can create a new branch explicitly based off

upstream/master:

$ git checkout -b issue-1755-fail2ban upstream/master

Switched to a new branch 'issue-1755-fail2ban'

Now you're ready to work on the issue or feature.

Run linters and tests locally

In addition to having Travis run tests and linters each time you push a new commit, you can also run them locally. See testing for details.

Stage changes

Recall that files tracked with Git have possible three states: committed, modified, and staged.

To prepare a commit, first add the files with changes that you want to include in your commit to your staging area. You add both new files and existing ones. You can also remove files from staging when necessary.

Get status of working directory

To see what files in the working directory have changes that have not been

staged, use git status.

If you have no changes in the working directory, you'll see something like this:

$ git status

On branch issue-123

nothing to commit, working directory clean

If you have unstaged changes, you'll see something like this:

On branch issue-123

Untracked files:

(use "git add <file>..." to include in what will be committed)

newfile.py

nothing added to commit but untracked files present (use "git add" to track)

Stage additions with git add

To add changes to your staging area, use git add <filename>. Because git add is all about staging the changes you want to commit, you use it to add

new files as well as files with changes to your staging area.

Continuing our example from above, after we run git add newfile.py, we'll see

the following from git status:

On branch issue-123

Changes to be committed:

(use "git reset HEAD <file>..." to unstage)

new file: newfile.py

You can view the changes in files you have staged with git diff --cached. To

view changes to files you haven't yet staged, just use git diff.

If you want to add all changes in the working directory, use git add -A

(documentation).

You can also stage changes using your graphical Git client.

If you stage a file, you can undo it with git reset HEAD <filename>. Here's

an example where we stage a file test3.txt and then unstage it:

$ git add test3.txt

On branch issue-1234

Changes to be committed:

(use "git reset HEAD <file>..." to unstage)

new file: test3.txt

$ git reset HEAD test3.txt

$ git status

On branch issue-1234

Untracked files:

(use "git add <file>..." to include in what will be committed)

test3.txt

nothing added to commit but untracked files present (use "git add" to track)

Stage deletions with git rm

To remove existing files from your repository, use git rm

(documentation). This command can either stage the file for

removal from your repository AND delete it from your working directory or just

stage the file for deletion and leave it in your working directory.

To stage a file for deletion and remove it from your working directory, use

git rm <filename>:

$ git rm test.txt

rm 'test.txt'

$ git status

On branch issue-1234

Changes to be committed:

(use "git reset HEAD <file>..." to unstage)

deleted: test.txt

$ ls test.txt

ls: No such file or directory

To stage a file for deletion and keep it in your working directory, use

git rm --cached <filename>:

$ git rm --cached test2.txt

rm 'test2.txt'

$ git status

On branch issue-1234

Changes to be committed:

(use "git reset HEAD <file>..." to unstage)

deleted: test2.txt

$ ls test2.txt

test2.txt

If you stage a file for deletion with the --cached option, and haven't yet

run git commit, you can undo it with git reset HEAD <filename>:

$ git reset HEAD test2.txt

Unfortunately, you can't restore a file deleted with git rm if you didn't use

the --cache option. However, git rm only deletes files it knows about.

Files you have never added to git won't be deleted.

Commit changes

When you've staged all your changes, you're ready to commit. You can do this

with git commit -m "My commit message." to include a commit message.

Here's an example of committing with the -m for a one-line commit message:

$ git commit -m "Add a test commit for docs."

[issue-123 173e17a] Add a test commit for docs.

1 file changed, 1 insertion(+)

create mode 100644 newfile.py

You can also use git commit without the -m option and your editor to open,

allowing you to easily draft a multi-line commit message.

How long your commit message should be depends on where you are in your work. Using short, one-line messages for commits related to in-progress work makes sense. For a commit that you intend to be final or that encompasses a significant amount or complex work, you should include a longer message.

Keep in mind that your commit should contain a 'minimal coherent idea' and have a quality commit message. See Zulip docs Commit Discipline and Commit messages for details.

Here's an example of a longer commit message that will be used for a pull request:

Integrate Fail2Ban.

Updates Zulip logging to put an unambiguous entry into the logs such

that fail2ban can be configured to look for these entries.

Tested on my local Ubuntu development server, but would appreciate

someone testing on a production install with more users.

Fixes #1755.

The first line is the summary. It's a complete sentence, ending in a period. It uses a present-tense action verb, "Integrate", rather than "Integrates" or "Integrating".

The following paragraphs are full prose and explain why and how the change was made. It explains what testing was done and asks specifically for further testing in a more production-like environment.

The final paragraph indicates that this commit addresses and fixes issue #1755. When you submit your pull request, GitHub will detect and link this reference to the appropriate issue. Once your commit is merged into zulip/master, GitHub will automatically close the referenced issue. See Closing issues via commit messages for details.

Make as many commits as you need to to address the issue or implement your feature.

Push your commits to GitHub

As you're working, it's a good idea to frequently push your changes to GitHub. This ensures your work is backed up should something happen to your local machine and allows others to follow your progress. It also allows you to work from multiple computers without losing work.

Pushing to a feature branch is just like pushing to master:

$ git push origin <branch-name>

Counting objects: 6, done.

Delta compression using up to 4 threads.

Compressing objects: 100% (4/4), done.

Writing objects: 100% (6/6), 658 bytes | 0 bytes/s, done.

Total 6 (delta 3), reused 0 (delta 0)

remote: Resolving deltas: 100% (3/3), completed with 1 local objects.

To git@github.com:christi3k/zulip.git

* [new branch] issue-demo -> issue-demo

If you want to see what git will do without actually performing the push, add

the -n (dry-run) option: git push -n origin <branch-name>. If everything

looks good, re-run the push command without -n.

If the feature branch does not already exist on GitHub, it will be created when

you push and you'll see * [new branch] in the command output.

Examine and tidy your commit history

Examining your commit history prior to submitting your pull request is a good idea. Is it tidy such that each commit represents a minimally coherent idea (see commit discipline)? Do your commit messages follow Zulip's style? Will the person reviewing your commit history be able to clearly understand your progression of work?

On the command line, you can use the git log command to display an easy to

read list of your commits:

$ git log --all --graph --oneline --decorate

* 4f8d75d (HEAD -> 1754-docs-add-git-workflow) docs: Add details about configuring Travis CI.

* bfb2433 (origin/1754-docs-add-git-workflow) docs: Add section for keeping fork up-to-date to Git Guide.

* 4fe10f8 docs: Add sections for creating and configuring fork to Git Guide.

* 985116b docs: Add graphic client recs to Git Guide.

* 3c40103 docs: Add stubs for remaining Git Guide sections.

* fc2c01e docs: Add git guide quickstart.

| * f0eaee6 (upstream/master) bug: Fix traceback in get_missed_message_token_from_address().

Alternatively, use your graphical client to view the history for your feature branch.

If you need to update any of your commits, you can do so with an interactive rebase. Common reasons to use an interactive rebase include:

- squashing several commits into fewer commits

- splitting a single commit into two or more

- rewriting one or more commit messages

There is ample documentation on how to rebase, so we won't go into details here. We recommend starting with GitHub's help article on rebasing and then consulting Git's documentation for git-rebase if you need more details.

If all you need to do is edit the commit message for your last commit, you can

do that with git commit --amend. See Git Basics - Undoing

Things for details on this and other useful commands.

Force-push changes to GitHub after you've altered your history

Any time you alter history for commits you have already pushed to GitHub,

you'll need to prefix the name of your branch with a +. Without this, your

updates will be rejected with a message such as:

$ git push origin 1754-docs-add-git-workflow

To git@github.com:christi3k/zulip.git

! [rejected] 1754-docs-add-git-workflow -> 1754-docs-add-git-workflow (non-fast-forward)

error: failed to push some refs to 'git@github.com:christi3k/zulip.git'

hint: Updates were rejected because the tip of your current branch is behind

hint: its remote counterpart. Integrate the remote changes (e.g.

hint: 'git pull ...') before pushing again.

hint: See the 'Note about fast-forwards' in 'git push --help' for details.

Re-running the command with +<branch> allows the push to continue by

re-writing the history for the remote repository:

$ git push origin +1754-docs-add-git-workflow

Counting objects: 12, done.

Delta compression using up to 4 threads.

Compressing objects: 100% (12/12), done.

Writing objects: 100% (12/12), 3.71 KiB | 0 bytes/s, done.

Total 12 (delta 8), reused 0 (delta 0)

remote: Resolving deltas: 100% (8/8), completed with 2 local objects.

To git@github.com:christi3k/zulip.git

+ 2d49e2d...bfb2433 1754-docs-add-git-workflow -> 1754-docs-add-git-workflow (forced update)

This is perfectly okay to do on your own feature branches, especially if you're the only one making changes to the branch. If others are working along with you, they might run into complications when they retrieve your changes because anyone who has based their changes off a branch you rebase will have to do a complicated rebase.

Create a pull request

When you're ready for feedback, submit a pull request. Pull requests are a feature specific to GitHub. They provide a simple, web-based way to submit your work (often called "patches") to a project. It's called a pull request because you're asking the project to pull changes from your fork.

If you're unfamiliar with how to create a pull request, you can check out GitHub's documentation on creating a pull request from a fork. You might also find GitHub's article about pull requests helpful. That all said, the tutorial below will walk you through the process.

Work in progress pull requests

In the Zulip project, we encourage submitting work-in-progress pull requests early and often. This allows you to share your code to make it easier to get feedback and help with your changes. Prefix the titles of work-in-progress pull requests with [WIP], which in our project means that you don't think your pull request is ready to be merged (e.g. it might not work or pass tests). This sets expectations correctly for any feedback from other developers, and prevents your work from being merged before you're confident in it.

Step 1: Update your branch with git rebase

The best way to update your branch is with git fetch and git rebase. Do not

use git pull or git merge as this will create merge commits. See keep your

fork up to date for details.

Here's an example (you would replace issue-123 with the name of your feature branch):

$ git checkout issue123

Switched to branch 'issue-123'

$ git fetch upstream

remote: Counting objects: 69, done.

remote: Compressing objects: 100% (23/23), done.

remote: Total 69 (delta 49), reused 39 (delta 39), pack-reused 7

Unpacking objects: 100% (69/69), done.

From https://github.com/zulip/zulip

69fa600..43e21f6 master -> upstream/master

$ git rebase upstream/master

First, rewinding head to replay your work on top of it...

Applying: troubleshooting tip about provisioning

Step 2: Push your updated branch to your remote fork

Once you've updated your local feature branch, push the changes to GitHub:

$ git push origin issue-123

Counting objects: 6, done.

Delta compression using up to 4 threads.

Compressing objects: 100% (4/4), done.

Writing objects: 100% (6/6), 658 bytes | 0 bytes/s, done.

Total 6 (delta 3), reused 0 (delta 0)

remote: Resolving deltas: 100% (3/3), completed with 1 local objects.

To git@github.com:christi3k/zulip.git

+ 2d49e2d...bfb2433 issue-123 -> issue-123

If your push is rejected with error failed to push some refs then you need

to prefix the name of your branch with a +:

$ git push origin +issue-123

Counting objects: 6, done.

Delta compression using up to 4 threads.

Compressing objects: 100% (4/4), done.

Writing objects: 100% (6/6), 658 bytes | 0 bytes/s, done.

Total 6 (delta 3), reused 0 (delta 0)

remote: Resolving deltas: 100% (3/3), completed with 1 local objects.

To git@github.com:christi3k/zulip.git

+ 2d49e2d...bfb2433 issue-123 -> issue-123 (forced update)

This is perfectly okay to do on your own feature branches, especially if you're the only one making changes to the branch. If others are working along with you, they might run into complications when they retrieve your changes because anyone who has based their changes off a branch you rebase will have to do a complicated rebase.

Step 3: Open the pull request

If you've never created a pull request or need a refresher, take a look at GitHub's article creating a pull request from a fork. We'll briefly review the process here.

The first step in creating a pull request is to use your web browser to navigate to your fork of Zulip. Sign in to GitHub if you haven't already.

Next, navigate to the branch you've been working on. Do this by clicking on the Branch button and selecting the relevant branch. Finally, click the New pull request button.

Alternatively, if you've recently pushed to your fork, you will see a green Compare & pull request button.

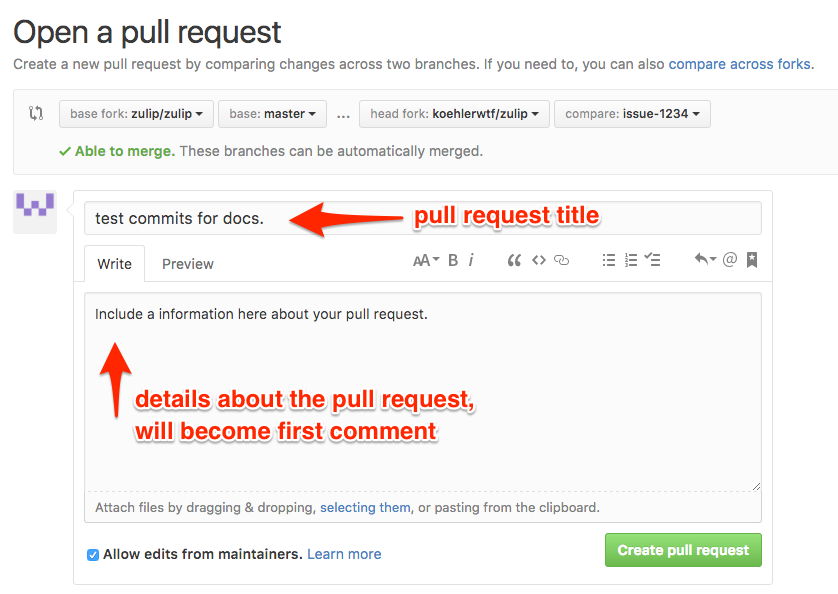

You'll see the Open a pull request page:

Provide a title and first comment for your pull request. Remember to prefix your pull request title with [WIP] if it is a work-in-progress.

If your pull request has an effect on the visuals of a component, you might want to include a screenshot of this change or a GIF of the interaction in your first comment. This will allow reviewers to comment on your changes without having to checkout your branch; you can find a list of tools you can use for this over here.

When ready, click the green Create pull request to submit the pull request.

Note: Pull request titles are different from commit messages. Commit

messages can be edited with git commit --amend, git rebase -i, etc., while

the title of a pull request can only be edited via GitHub.

Update a pull request

As you get make progress on your feature or bugfix, your pull request, once submitted, will be updated each time you push commits to your remote branch. This means you can keep your pull request open as long as you need, rather than closing and opening new ones for the same feature or bugfix.

It's a good idea to keep your pull request mergeable with Zulip upstream by frequently fetching, rebasing, and pushing changes. See keep your fork up to date for details. You might also find this excellent article How to Rebase a Pull Request helpful.

And, as you address review comments others have made, we recommend posting a follow-up comment in which you: a) ask for any clarifications you need, b) explain to the reviewer how you solved any problems they mentioned, and c) ask for another review.

Collaborate

Fetch another contributor's branch

What happens when you would like to collaborate with another contributor and they have work-in-progress on their own fork of Zulip? No problem! Just add their fork as a remote and pull their changes.

$ git remote add <username> https://github.com/<username>/zulip.git

$ git fetch <username>

Now you can checkout their branch just like you would any other. You can name the branch anything you want, but using both the username and branch name will help you keep things organized.

$ git checkout -b <username>/<branchname>

You can choose to rename the branch if you prefer:

git checkout -b <custombranchname> <username>/<branchname>

Checkout a pull request locally

Just as you can checkout any user's branch locally, you can also checkout any pull request locally. GitHub provides a special syntax (details) for this since pull requests are specific to GitHub rather than Git.

First, fetch and create a branch for the pull request, replacing ID and BRANCHNAME with the ID of the pull request and your desired branch name:

$ git fetch upstream pull/ID/head:BRANCHNAME

Now switch to the branch:

$ git checkout BRANCHNAME

Now you work on this branch as you would any other.

Note: you can use the scripts provided in the tools/ directory to fetch pull requests. You can read more about what they do here.

tools/fetch-rebase-pull-request <PR-number>

tools/fetch-pull-request <PR-number>

Review changes

Changes on (local) working tree

Display changes between index and working tree (what is not yet staged for commit):

$ git diff

Display changes between index and last commit (what you have staged for commit):

$ git diff --cached

Display changes in working tree since last commit (changes that are staged as well as ones that are not):

$ git diff HEAD

Changes within branches

Use any git-ref to compare changes between two commits on the current branch.

Display changes between commit before last and last commit:

$ git diff HEAD^ HEAD

Display changes between two commits using their hashes:

$ git diff e2f404c 7977169

Changes between branches

Display changes between tip of topic branch and tip of master branch:

$ git diff topic master

Display changes that have occurred on master branch since topic branch was created:

$ git diff topic...master

Display changes you've committed so far since creating a branch from upstream/master:

$ git diff upstream/master...HEAD

Get and stay out of trouble

Git is a powerful yet complex version control system. Even for contributors experienced at using version control, it can be confusing. The good news is that nearly all Git actions add information to the Git database, rather than removing it. As such, it's hard to make Git perform actions that you can't undo. However, git can't undo what it doesn't know about, so it's a good practice to frequently commit your changes and frequently push your commits to your remote repository.

Undo a merge commit

A merge commit is a special type of commit that has two parent commits. It's created by Git when you merge one branch into another and the last commit on your current branch is not a direct ancestor of the branch you are trying to merge in. This happens quite often in a busy project like Zulip where there are many contributors because upstream/zulip will have new commits while you're working on a feature or bugfix. In order for Git to merge your changes and the changes that have occurred on zulip/upstream since you first started your work, it must perform a three-way merge and create a merge commit.

Merge commits aren't bad, however, Zulip don't use them. Instead Zulip uses a forked-repo, rebase-oriented workflow.

A merge commit is usually created when you've run git pull or git merge.

You'll know you're creating a merge commit if you're prompted for a commit

message and the default is something like this:

Merge branch 'master' of https://github.com/zulip/zulip

# Please enter a commit message to explain why this merge is necessary,

# especially if it merges an updated upstream into a topic branch.

#

# Lines starting with '#' will be ignored, and an empty message aborts

# the commit.

And the first entry for git log will show something like:

commit e5f8211a565a5a5448b93e98ed56415255546f94

Merge: 13bea0e e0c10ed

Author: Christie Koehler <ck@christi3k.net>

Date: Mon Oct 10 13:25:51 2016 -0700

Merge branch 'master' of https://github.com/zulip/zulip

Some graphical Git clients may also create merge commits.

To undo a merge commit, first run git reflog to identify the commit you want

to roll back to:

$ git reflog

e5f8211 HEAD@{0}: pull upstream master: Merge made by the 'recursive' strategy.

13bea0e HEAD@{1}: commit: test commit for docs.

Reflog output will be long. The most recent git refs will be listed at the top.

In the example above e5f8211 HEAD@{0}: is the merge commit made automatically

by git pull and 13bea0e HEAD@{1}: is the last commit I made before running

git pull, the commit that I want to rollback to.

Once you'd identified the ref you want to revert to, you can do so with git reset:

$ git reset --hard 13bea0e

HEAD is now at 13bea0e test commit for docs.

Important: git reset --hard <commit> will discard all changes in your

working directory and index since the commit you're resetting to with

. This is the main way you can lose work in Git. If you need to

keep any changes that are in your working directory or that you have committed,

use git reset --merge <commit> instead.

You can also use the relative reflog HEAD@{1} instead of the commit hash,

just keep in mind this changes as you run git commands.

Now when I look at the git reflog, I see the tip of my branch is pointing to my

last commit 13bea0e before the merge:

$ git reflog

13bea0e HEAD@{2}: reset: moving to HEAD@{1}

e5f8211 HEAD@{3}: pull upstream master: Merge made by the 'recursive' strategy.

13bea0e HEAD@{4}: commit: test commit for docs.

And the first entry git log shows is this:

commit 13bea0e40197b1670e927a9eb05aaf50df9e8277

Author: Christie Koehler <ck@christi3k.net>

Date: Mon Oct 10 13:25:38 2016 -0700

test commit for docs.

Restore a lost commit

We've mentioned you can use git reset --hard to rollback to a previous

commit. What if you run git reset --hard and then realize you actually need

one or more of the commits you just discarded? No problem, you can restore them

with git cherry-pick (docs).

For example, let's say you just committed "some work" and your git log looks

like this:

* 67aea58 (HEAD -> master) some work

* 13bea0e test commit for docs.

You then mistakenly run git reset --hard 13bea0e:

$ git reset --hard 13bea0e

HEAD is now at 13bea0e test commit for docs.

$ git log

* 13bea0e (HEAD -> master) test commit for docs.

And then realize you actually needed to keep commit 67aea58. First, use git reflog to confirm that commit you want to restore and then run git cherry-pick <commit>:

$ git reflog

13bea0e HEAD@{0}: reset: moving to 13bea0e

67aea58 HEAD@{1}: commit: some work

$ git cherry-pick 67aea58

[master 67aea58] some work

Date: Thu Oct 13 11:51:19 2016 -0700

1 file changed, 1 insertion(+)

create mode 100644 test4.txt

Recover from a git rebase failure

One situation in which git rebase will fail and require you to intervene is

when your change, which git will try to re-apply on top of new commits from

which ever branch you are rebasing on top of, is to code that has been changed

by those new commits.

For example, while I'm working on a file, another contributor makes a change to

that file, submits a pull request and has their code merged into master.

Usually this is not a problem, but in this case the other contributor made a

change to a part of the file I also want to change. When I try to bring my

branch up to date with git fetch and then git rebase upstream/master, I see

the following:

First, rewinding head to replay your work on top of it...

Applying: test change for docs

Using index info to reconstruct a base tree...

M README.md

Falling back to patching base and 3-way merge...

Auto-merging README.md

CONFLICT (content): Merge conflict in README.md

error: Failed to merge in the changes.

Patch failed at 0001 test change for docs

The copy of the patch that failed is found in: .git/rebase-apply/patch

When you have resolved this problem, run "git rebase --continue".

If you prefer to skip this patch, run "git rebase --skip" instead.

To check out the original branch and stop rebasing, run "git rebase --abort".

This message tells me that Git was not able to apply my changes to README.md after bringing in the new commits from upstream/master.

Running git status also gives me some information:

rebase in progress; onto 5ae56e6

You are currently rebasing branch 'docs-test' on '5ae56e6'.

(fix conflicts and then run "git rebase --continue")

(use "git rebase --skip" to skip this patch)

(use "git rebase --abort" to check out the original branch)

Unmerged paths:

(use "git reset HEAD <file>..." to unstage)

(use "git add <file>..." to mark resolution)

both modified: README.md

no changes added to commit (use "git add" and/or "git commit -a")

To fix, open all the files with conflicts in your editor and decide which edits

should be applied. Git uses standard conflict-resolution (<<<<<<<, =======,

and >>>>>>>) markers to indicate where in files there are conflicts.

Once you've done that, save the file(s), stage them with git add and then

continue the rebase with git rebase --continue:

$ git add README.md

$ git rebase --continue

Applying: test change for docs

For help resolving merge conflicts, see basic merge conflicts, advanced merging, and/or GitHub's help on how to resolve a merge conflict.

Working from multiple computers

Working from multiple computers with Zulip and Git is fine, but you'll need to pay attention and do a bit of work to ensure all of your work is readily available.

Recall that most Git operations are local. When you commit your changes with

git commit they are safely stored in your local Git database only. That is,

until you push the commits to GitHub, they are only available on the computer

where you committed them.

So, before you stop working for the day, or before you switch computers, push

all of your commits to GitHub with git push:

$ git push origin <branchname>

When you first start working on a new computer, you'll clone the Zulip repository and connect it to Zulip upstream. A clone retrieves all current commits, including the ones you pushed to GitHub from your other computer.

But if you're switching to another computer on which you have already cloned

Zulip, you need to update your local Git database with new refs from your

GitHub fork. You do this with git fetch:

$ git fetch <usermame>

Ideally you should do this before you have made any commits on the same branch

on the second computer. Then you can git merge on whichever branch you need

to update:

$ git checkout <my-branch>

Switched to branch '<my-branch>'

$ git merge origin/master

If you have already made commits on the second computer that you need to

keep, you'll need to use git log FETCH_HEAD to identify that hashes of the

commits you want to keep and then git cherry-pick <commit> those commits into

whichever branch you need to update.

Zulip-specific tools

This section will document the zulip-specific git tools contributors will find helpful.

Set up git repo script

In the tools directory of zulip/zulip you'll find a

bash script setup-git-repo. This script installs the Zulip pre-commit hook.

This hook will run each time you git commit to automatically run linters,

etc. The hook passes no matter the result of the linter, but you should still

pay attention to any notices or warnings it displays.

It's simple to use. Make sure you're in the clone of zulip and run the following:

$ ./tools/setup-git-repo

The script doesn't produce any output if successful. To check that the hook has

been installed, print a directory listing for .git/hooks and you should see

something similar to:

$ ls -l .git/hooks

pre-commit -> ../../tools/pre-commit

Reset to pull request

tools/reset-to-pull-request is a short-cut for checking out a pull request

locally. It works slightly differently from the method

described above in that it does not create a branch for the pull request

checkout.

This tool checks for uncommitted changes, but it will move the

current branch using git reset --hard. Use with caution.

First, make sure you are working in a branch you want to move (in this

example, we'll use the local master branch). Then run the script

with the ID number of the pull request as the first argument.

$ git checkout master

Switched to branch 'master'

Your branch is up-to-date with 'origin/master'.

$ ./tools/reset-to-pull-request 1900

+ request_id=1900

+ git fetch upstream pull/1900/head

remote: Counting objects: 159, done.

remote: Compressing objects: 100% (17/17), done.

remote: Total 159 (delta 94), reused 91 (delta 91), pack-reused 51

Receiving objects: 100% (159/159), 55.57 KiB | 0 bytes/s, done.

Resolving deltas: 100% (113/113), completed with 54 local objects.

From https://github.com/zulip/zulip

* branch refs/pull/1900/head -> FETCH_HEAD

+ git reset --hard FETCH_HEAD

HEAD is now at 2bcd1d8 troubleshooting tip about provisioning

Fetch a pull request and rebase

tools/fetch-rebase-pull-request is a short-cut for checking out a pull

request locally in its own branch and then updating it with any

changes from upstream/master with git rebase.

Run the script with the ID number of the pull request as the first argument.

$ tools/fetch-rebase-pull-request 1913

+ request_id=1913

+ git fetch upstream pull/1913/head

remote: Counting objects: 4, done.

remote: Compressing objects: 100% (4/4), done.

remote: Total 4 (delta 0), reused 0 (delta 0), pack-reused 0

Unpacking objects: 100% (4/4), done.

From https://github.com/zulip/zulip

* branch refs/pull/1913/head -> FETCH_HEAD

+ git checkout upstream/master -b review-1913

Branch review-1913 set up to track remote branch master from upstream.

Switched to a new branch 'review-1913'

+ git reset --hard FETCH_HEAD

HEAD is now at 99aa2bf Add provision.py fails issue in common erros

+ git pull --rebase

Current branch review-1913 is up to date.

Fetch a pull request without rebasing

tools/fetch-pull-request is a similar to tools/fetch-rebase-pull-request, but

it does not rebase the pull request against upstream/master, thereby getting

exactly the same repository state as the commit author had.

Run the script with the ID number of the pull request as the first argument.

$ tools/fetch-pull-request 5156

+ git diff-index --quiet HEAD

+ request_id=5156

+ remote=upstream

+ git fetch upstream pull/5156/head

From https://github.com/zulip/zulip

* branch refs/pull/5156/head -> FETCH_HEAD

+ git checkout -B review-original-5156

Switched to a new branch 'review-original-5156'

+ git reset --hard FETCH_HEAD

HEAD is now at 5a1e982 tools: Update clean-branches to clean review branches.

Delete unimportant branches

tools/clean-branches is a shell script that removes branches that are either:

- Local branches that are ancestors of origin/master.

- Branches in origin that are ancestors of origin/master and named like

$USER-*. - Review branches created by

tools/fetch-rebase-pull-requestandtools/fetch-pull-request.

First, make sure you are working in branch master. Then run the script without any

arguments for default behavior. Since removing review branches can inadvertently remove any

feature branches whose names are like review-*, it is not done by default. To

use it, run tools/clean-branches --reviews.

$ tools/clean-branches --reviews

Deleting local branch review-original-5156 (was 5a1e982)